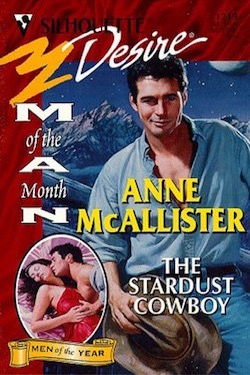

Excerpt: The Stardust Cowboy

Code of the West

Chapter One

Riley Stratton hated weddings.

So standing outside the reception of a couple of people he didn’t even know was an irritation right off. They looked so damned happy. So fresh and bright and cheerful — as if they had the world by the tail.

Riley sometimes felt as if he had the world by the hooves — and all four were about to stomp him into the dirt.

He had enough to deal with. He didn’t need a wedding as well.

You didn’t have to see it, he reminded himself. Just because Dori Malone’s neighbor had said that’s where she was, he hadn’t had to come running over.

It was just that he wanted to get it done.

He wanted to break the news about Chris, tell her about the ranch, get her agreement to sell, and head home, so that tomorrow his life would be back to normal again and he’d have nothing more to worry about than working his cattle.

And — incidentally — he wanted to see the boy.

The boy.

He’d stood in the shadows when the wedding guests had come outside and flanked the steps while bride and groom ran down between them amid a shower of rice and bird seed and glitter. Everyone else had been watching the wedding couple.

Riley had been scanning the guests for a boy.

He’d be close to eight now. There had been several pictures of him in the small bundle of letters that had come last week in the mail. They had been part of what he supposed were his brother, Chris’s, “effects.”

Until then it had been impossible to think of Chris as being dead. Impossible to believe that his brother wasn’t out there somewhere, driving like a maniac, playing his guitar like an angel, singing up a storm. He’d been gone from home so long — ten years — and had come back so rarely, that Riley had long ago got used to not having him around.

But he hadn’t been able to think of his little brother as dead — not even when the very official, notarized certificate arrived from Arizona, where Chris had lived and worked for the past year.

Riley hadn’t really fathomed it until he opened the first of the thin bundle of envelopes rubber banded together and five snapshots had fallen out. Chris, he’d thought at first, because the little brown-haired, blue-eyed boy in the photos looked very much like his brother.

But it wasn’t Chris.

Jake was the name on the back of the photos: Jake at four months; Jake’s first birthday; Jake at three; Jake in kindergarten; Jake, a gap-toothed seven.

Who the hell was Jake?

Scowling, Riley had fumbled the envelopes open and unfolded the letters — first one, then the next, until he’d read them all. There were five, written in a neat feminine hand, and they explained to Riley what Chris never had.

The boy — Jake — was Chris’s son.

That’s when Chris’s death had become real.

It was as though, if his brother could have kept such a monumental secret for so many years, he didn’t really exist the way Riley had always thought of him, anyway.

And thinking of the vital, vigorous, hell-bent-for-the-horizon, Chris dead and still as the result of a car wreck on a steep mountain road didn’t seem any stranger than thinking of his brother as the father of an almost-eight year old son.

The more Riley thought about it, though, knowing about Jake made sense of a lot of things Chris had done and said the past few years.

Jake must have been in his mind when, after their father’s death four years ago, Chris had declined to sell Riley his half of the ranch. “Nope, I can’t,” he’d said with his customary blitheness.

“Why the hell not?” Riley had been shocked, unable to understand why Chris would want to hang onto a ranch he’d been desperate to leave ever since he was fifteen.

“It’s my legacy,” Chris had said. “I might want to hand it on to my own kids someday.”

Riley remembered thinking that Chris settling down long enough to marry and have kids was a pretty unlikely prospect. He’d even said as much.

Chris had grinned. “You never know.”

Obviously you never did.

Certainly Riley hadn’t.

Back then Chris’s son must have already been four years old.

Two of the most recent letters thanked Chris for money he’d sent. And that explained a lot, too. Riley hadn’t understood why, if Chris was so determined to hang onto his share of the ranch, he’d been so unwilling to plow any of the profits of his share back in.

“I’ve got other priorities,” was all Chris had said.

And all of Riley’s scornful comments about Chris’s fast lane lifestyle had had no effect. All his common sense and logic had been wasted on Chris, he’d thought at the time.

Now he realized that Chris had had other priorities, other obligations.

You could have said, he told his brother silently. You could have told me you had a son.

But even as he thought it, he knew why Chris hadn’t. His brother would never have admitted to a son he wasn’t seeing, a son whose mother he hadn’t married, a responsibility that he didn’t want Riley haranguing him about.

And Riley would have harangued.

Responsibility, Chris had once complained, was Riley’s middle name. “Prob’ly was your first name. They just couldn’t spell it.”

In Riley’s opinion it wouldn’t have hurt Chris to have been a little more responsible now and then. In the instance of Jake, apparently he had been.

Sort of.

But he hadn’t left a will. It would never have occurred to Chris to leave a will. He’d always considered himself invulnerable, unassailable, immortal. What thirty year old believes he’s ever going to die?

But he had died. And for almost a month Riley had thought he was Chris’s heir. The sole survivor. The owner of the Stratton ranch.

Legally he might be able to pretend he still was. Chris had never married the mother of his son. Marriage had never been a part of Chris’s plans.

He was, in his own words, “a rolling stone — lower case.”

He was a musician, like the upper case ones, but the similarity ended there. Chris’s music had tended toward cowboy ballads and honky-tonk tunes. A lot of them he had written himself, and Riley knew little enough about music to be impressed.

But what always impressed him more was Chris’s determination. From the time he’d been a little boy, Chris had had his sights set on the horizon — on moving out, moving on — and making a name for himself.

“I ain’t gonna be no two-bit cowboy,”he’d told Riley so often that it began to sound like the refrain to one of his songs.

Not like you. Chris could never understand why Riley wasn’t chomping at the bit to be gone. For years Chris had been counting the days until he graduated from high school and could kick the dust from his boots and head on down the road.

“At least you got as far as Laramie,” he said to Riley when his brother went away to college.

But college hadn’t lasted but three years. Right after Chris’s long-anticipated graduation and departure, their father had taken the fall from the horse that had crippled him.

There had been no one else to help out — no aunts, uncles or cousins — just him and Chris. So Riley had come home.

Chris hadn’t.

“No way,” he’d said when Riley had finally tracked him down through a series of messages and long-distance phone calls. “You’re not gettin’ me back there. You do it if you want, but it won’t just be while Dad’s laid up. It’ll be forever. You’re done for,” he’d told Riley flatly. “You go back and you’re stuck. For good. You’re never gonna get away now.”

Riley hadn’t cared.

He’d always loved the ranch as much as Chris had hated it. And besides, he’d been fool enough to think that Tricia would come home with him.

Tricia …

No, goddammit, he wasn’t going to start thinking about Tricia tonight!

He had enough to think about, just contemplating what he had to say to Chris’s lover — and to his child.

But he wasn’t going to be saying it at any wedding reception. He’d wait until they got home. It wouldn’t be that late. A responsible mother wouldn’t keep her kid out until all hours. And from her letters, Riley had determined however big a fool she’d been for loving his brother, in matters of parenthood, Dori Malone was definitely responsible and sensible.

He was glad. It would make telling her easier. And it would make her selling out to him a foregone conclusion.

He tucked his hands into his jacket pockets, he strode away down the sidewalk toward his truck.